Response Doctoral Program

As the need for climate change mitigation intensifies, a crucial challenge emerges: how do we tackle the menace of carbon dioxide emissions? One promising solution is Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS), a technology by which carbon dioxide emissions are captured and stored deep underground in rock formations or depleted oil wells. While CCS holds significant potential for curbing industrial contributions to climate change, it demands suitable underground storage space for the captured carbon dioxide, which is accompanied by two major hurdles. First, identifying these locations is challenging because storing carbon dioxide requires special geological conditions underground. Second, this may give rise to “Not-In-My-Backyard” protests in communities that host carbon dioxide storage projects due to public misperceptions of carbon dioxide as toxic for individuals.

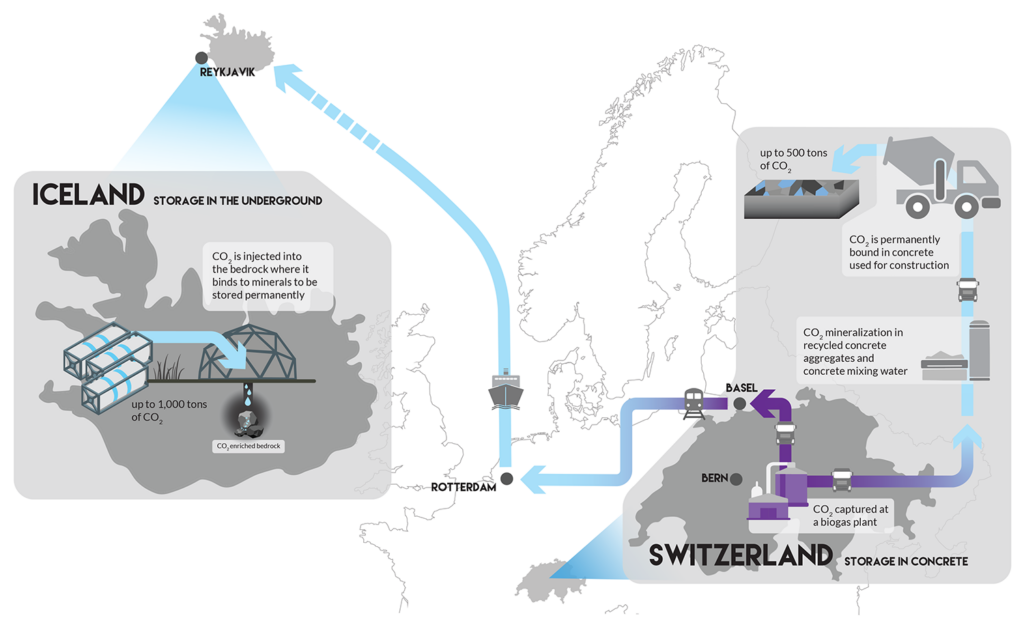

Given geological limitations in many countries, international cooperation is essential to scale up the carbon dioxide storage potential in time to mitigate climate change. Cross-border cooperation on CCS involves capturing carbon dioxide in one country but storing it in another. A first successful demonstration project transported carbon dioxide from Switzerland to Iceland (Fig, 1). In addition, the European Union plans a carbon dioxide pipeline network to transport carbon dioxide from emitter countries to those that will store it.

While storing carbon dioxide abroad is becoming a key element of climate policy in several countries, public support for the geological storage of carbon dioxide remains low in many European countries. Protests in Germany, for example, prevented large CCS projects. Not only is the public often reluctant to support domestic CCS projects, but public opinion polls imply that cross-border cooperation on CCS is even less popular among these stakeholders. Therefore, understanding the conditions that generate public support for international cooperation on CCS is crucial to ensure the political feasibility of these projects. It also empowers policymakers to navigate the delicate balance between implementing essential political actions and aligning with what citizens deem acceptable—a crucial aspect of functioning democracies.

Susanne Rhein is a PhD student at ETH Zurich in the International Political Economy and Environmental Politics group, as well as a RESPONSE fellow in the PhD program Science and Policy. In cooperation with her co-author Thomas Bernauer she sought to understand public perceptions of CCS projects and ways to garner further support for them through her research.

The Role of Public Support

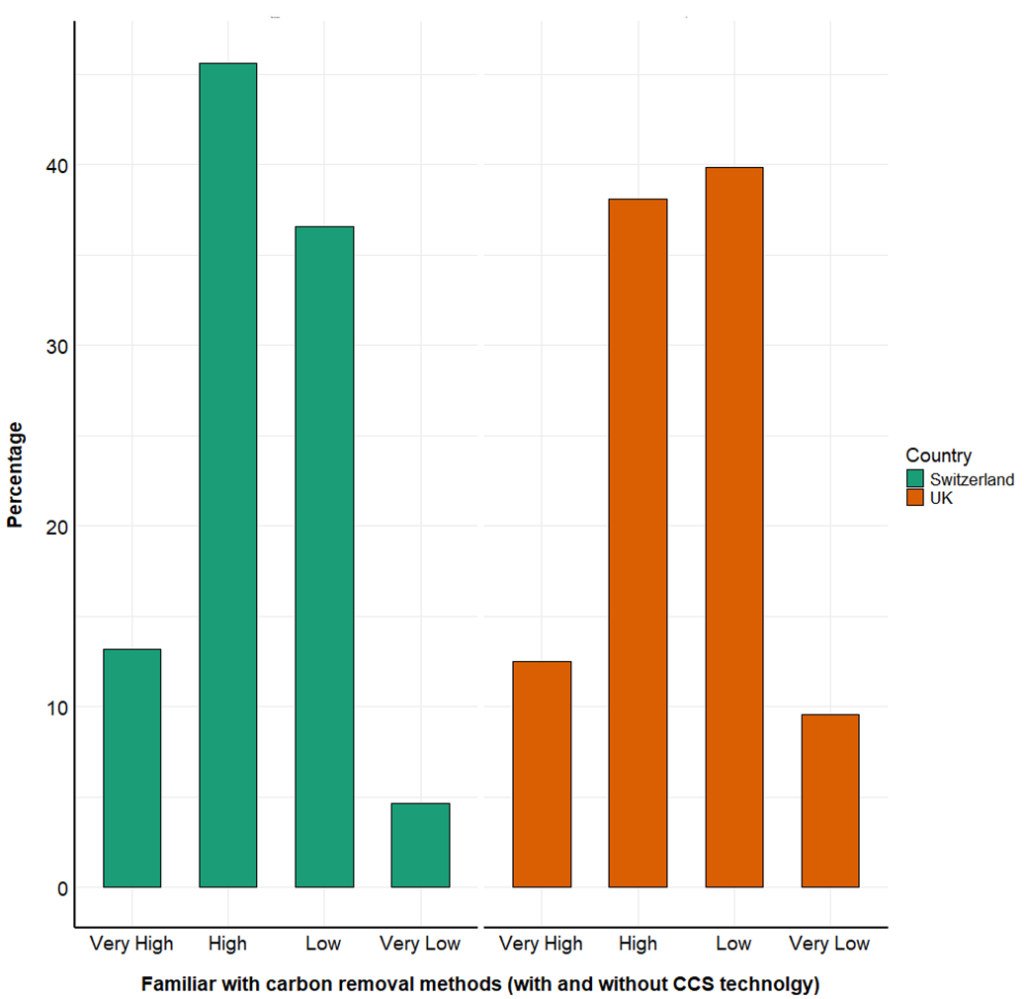

According to our survey study fielded among 3,000 participants in Switzerland and the UK, public support for exporting carbon dioxide (CO2) for storage abroad depends heavily on the costs and the choice of partner countries. This study by Susanne Rhein and Thomas Bernauer assessed participants’ knowledge on CCS and support for CO2 storage projects at home and abroad. Furthermore, the experiment examined the effects of storage costs and partner country characteristics—such as regime type, climate policy ambition, distance of a CO2 storage site from the next city, and geographical region—on public support for CO2 storage abroad. We found only half of respondents were aware of CCS technologies (Fig. 2), with most associating carbon dioxide removal with nature-based methods like tree planting. This underscores the need for public education to dispel misconceptions and build support for international CCS projects.

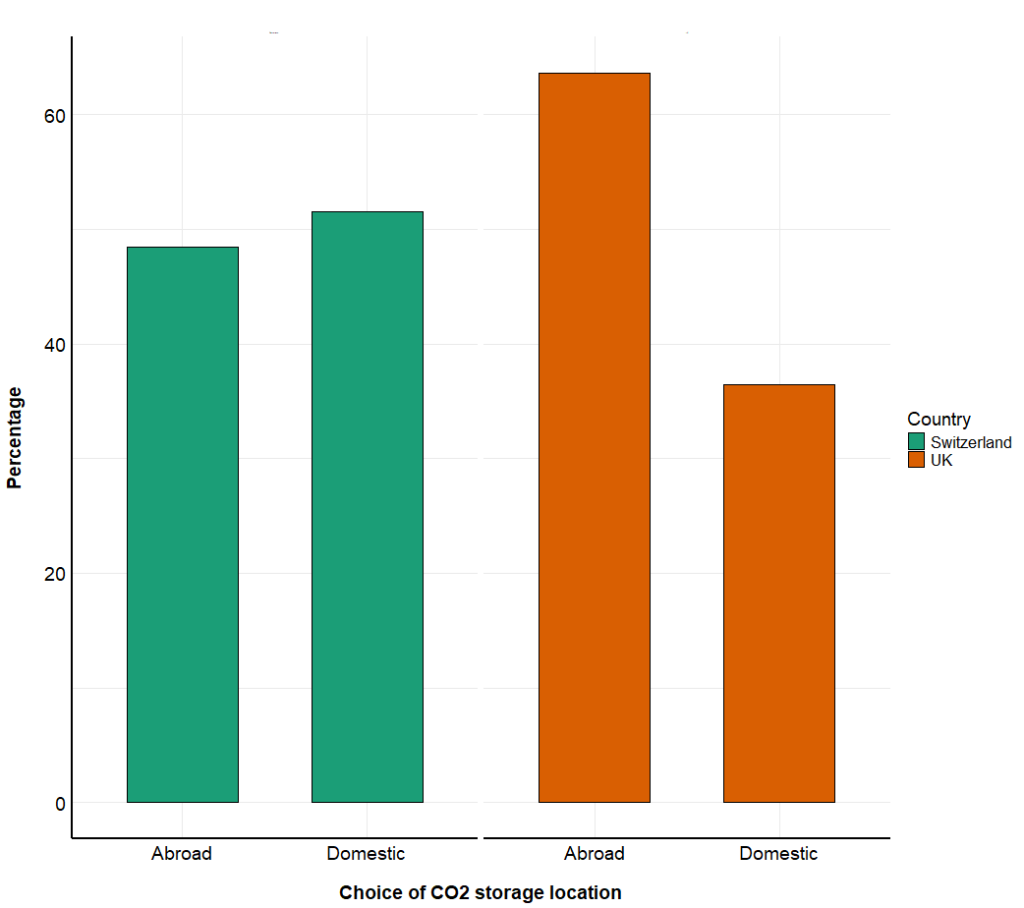

The study also implies that support for storing CO2 abroad is higher in the UK compared to Switzerland where study participants were slightly more likely to prefer CO2 storage at home (Fig, 3). Focusing on identifying citizens’ preferred partner country for cross-border CO2 trade, the study also implies that public support for CCS projects abroad varies significantly—by up to 45%—depending on partner country characteristics. Support increases for democratic countries with ambitious climate policies, and greater distances from population centers. As such partners increase the credibility of such projects, this even increases study participants’ willingness to pay for storage abroad. Conversely, there is strong opposition to low-cost storage in less democratic nations with weak climate policies or higher risks for local populations.

These results challenge the “Not In My Backyard” argument, suggesting that public concern about the risk of CO2 storage is not just about CCS projects close by. Citizens remain concerned about the quality and safety of CCS projects even when they are conducted abroad. Hence, choosing credible partners is key to gaining public backing for such projects, even at higher costs.

Implications for Policymakers

European countries need to significantly increase their carbon dioxide storage capacity, by up to 48 gigatons by 2030, which requires swift international cooperation and the development of new cross-border infrastructure. Despite the urgency, these results highlight the need for careful partner country selection when designing cross-border CCS strategies. Policymakers should not assume that exporting captured carbon dioxide is a quick fix for overcoming public opposition to domestic CCS projects. The study shows that the public prefers cooperation with democratic countries that have strong climate policies, even if this comes at a higher price. Emerging cross-border cooperation on CCS reflects these preferences, with countries like Sweden, Iceland and the Netherlands planning to import substantial amounts of carbon dioxide from Switzerland and Germany.

Susanne Rhein is a fellow of the RESPONSE Doctoral Program (DP) «RESPONSE – to society and policy needs through plant, food and energy sciences» funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Grant Agreement No 847585.