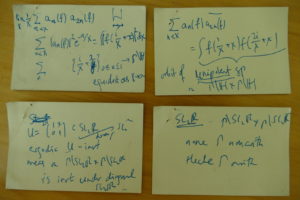

In the course of writing our paper on the support of the Kloosterman paths, Will Sawin and I encountered some very beautiful classical questions of Fourier analysis. As discussed in the previous post, we were interested in the following question: given a continuous function ![f \colon [0,1]\to \mathbf{C} f \colon [0,1]\to \mathbf{C}](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=f+%5Ccolon+%5B0%2C1%5D%5Cto+%5Cmathbf%7BC%7D&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0) , such that (1) we have

, such that (1) we have ![f(1)\in [-2,2]\subset \mathbf{R} f(1)\in [-2,2]\subset \mathbf{R}](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=f%281%29%5Cin+%5B-2%2C2%5D%5Csubset+%5Cmathbf%7BR%7D&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0) and (2) the function

and (2) the function  has purely imaginary Fourier coefficients

has purely imaginary Fourier coefficients  for

for  , does there exist an increasing homeomorphism

, does there exist an increasing homeomorphism ![\sigma\colon [0,1]\to [0,1] \sigma\colon [0,1]\to [0,1]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Csigma%5Ccolon+%5B0%2C1%5D%5Cto+%5B0%2C1%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0) , such that

, such that  , and such that the new function

, and such that the new function  , in addition to the analogue of (1) and (2), also satisfies

, in addition to the analogue of (1) and (2), also satisfies  for

for  ?

?

After some searching we found the right keywords, or mathematical attractor, for this type of problem. It starts with a short paper of Gyula, alias Julius, alias Jules, Pál, alias Pal, alias Perl, in 1914, who attributes to Fejér the following question : can one reparameterize a continuous periodic function in such a way that the new function has uniformly convergent Fourier series? Pál shows that he can almost do it: his reparameterized function has Fourier series that converges uniformly on ![[\delta,1-\delta] [\delta,1-\delta]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5B%5Cdelta%2C1-%5Cdelta%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0) , where

, where  can be arbitrarily small (but the change of variable depends on

can be arbitrarily small (but the change of variable depends on  ).

).

This Theorem of Pál becomes the Bohr–Pál Theorem after Harald Bohr’s full answer to Fejér’s question in Acta Universitatis Szegediensis in 1935. (Note: I had never looked before at the archive of this particular journal; like most mathematical journals of this period, it is amazing how many names, and even theorems, one can recognize in almost any issue !)

Then comes a beautiful very short proof by Salem in 1944 (it is also the proof found in Zygmund’s book on trigonometric series). All three proofs rely on two results to achieve uniform convergence: one is Riemann’s mapping theorem, and the second is a result of Fejér, according to which the conformal map from the unit disc to the “interior” of a simple closed curve has the property that the boundary Fourier series converges uniformly. In fact, one can certainly write beautiful exercises or exams based on Salem’s proof, for a course in complex analysis that goes as far as Riemann’s Theorem…

The story does not stop here. It is amusing to note that none of Pál, Bohr or Salem feel that it is necessary to point out that they work with real-valued periodic functions. But this is essential to the basic structure of their argument (which starts by viewing  as the imaginary part of a complex number that describes a simple closed curve in

as the imaginary part of a complex number that describes a simple closed curve in  , the trick being to define the real part in a suitable way). Whether the Bohr-Pál Theorem holds for complex-valued functions

, the trick being to define the real part in a suitable way). Whether the Bohr-Pál Theorem holds for complex-valued functions  was an open problem until the late 1970’s (see for instance p. 128 of this 1974 survey of Zalcman about real and complex problems in analysis), when it was proved by Kahane and Katznelson with a completely different approach. They in fact succeeded in proving that one can find a single change of variable

was an open problem until the late 1970’s (see for instance p. 128 of this 1974 survey of Zalcman about real and complex problems in analysis), when it was proved by Kahane and Katznelson with a completely different approach. They in fact succeeded in proving that one can find a single change of variable  that transforms simultaneously all functions in a compact set of the space of (real-valued periodic) continuous functions into functions with uniformly convergent Fourier series; applied to the real and imaginary parts of a complex-valued function, this gives the required extension.

that transforms simultaneously all functions in a compact set of the space of (real-valued periodic) continuous functions into functions with uniformly convergent Fourier series; applied to the real and imaginary parts of a complex-valued function, this gives the required extension.

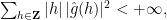

Coming back to our original question, the complex-variable proofs give some information on the Fourier coefficients of the reparameterized function  , precisely they imply that

, precisely they imply that

which is encouraging, even if no pointwise estimate follows. But some variants of the question have been studied that get much closer to what we want. They are discussed (among other things) in a nice survey by Olevskii. I find especially fascinating one theorem of Olevskii himself, published in 1981: it is not always possible to find a change of variable (of a real-valued periodic continuous function) so that the reparameterized function has an absolutely convergent Fourier series. This answers a question of Luzin, and is explained in Section 3 of Olevskii’s survey. Interestingly, this problem is now, of course, easier for complex-valued functions, compared to real-valued functions, and it was also solved by Kahane and Katznelson in the  -valued case.

-valued case.

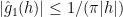

The result that turned out to be most useful for our purposes is

due to Sahakyan (whose name is also spelled Saakjan or Saakyan). He proves the existence of reparameterizations  of a continuous periodic function

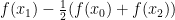

of a continuous periodic function  satisfying various asymptotic bounds for their Fourier coefficients. The result is here also restricted to real-valued functions, and again for a clear reason: the construction relies crucially on the intermediate value theorem for continuous functions. More precisely, Sahakyan’s idea is to use the Faber-Schauder expansions of continuous functions, and to find a change of variable that leads to a function

satisfying various asymptotic bounds for their Fourier coefficients. The result is here also restricted to real-valued functions, and again for a clear reason: the construction relies crucially on the intermediate value theorem for continuous functions. More precisely, Sahakyan’s idea is to use the Faber-Schauder expansions of continuous functions, and to find a change of variable that leads to a function  with a “sparse” Faber-Schauder expansion, from which he estimates directly the Fourier coefficients using bounds for those of the Faber-Schauder functions. (I actually didn’t know about Faber-Schauder expansions before; I will also certainly make use of them for analysis or functional analysis exercises later…) This works because the Faber-Schauder coefficients are quite simple: they are of the form

with a “sparse” Faber-Schauder expansion, from which he estimates directly the Fourier coefficients using bounds for those of the Faber-Schauder functions. (I actually didn’t know about Faber-Schauder expansions before; I will also certainly make use of them for analysis or functional analysis exercises later…) This works because the Faber-Schauder coefficients are quite simple: they are of the form

for suitable real numbers ![x_i\in [0,1] x_i\in [0,1]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=x_i%5Cin+%5B0%2C1%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0) . One can now easily imagine how the intermediate value theorem will make it possible to find a change of variable to make such a coefficient vanish.

. One can now easily imagine how the intermediate value theorem will make it possible to find a change of variable to make such a coefficient vanish.

Using Sahakyan’s main lemma, with a few modifications to take into account the additional symmetry we require, we were able to solve our reparameterization problem for the support of Kloosterman paths, in the case of real-valued functions. The complex-value case, as far as we know, remains open…