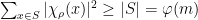

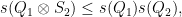

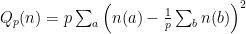

The inequality I was pondering during my recent vacations is another result of Burnside: for a finite cyclic group  , denoting by

, denoting by  the set of generators of

the set of generators of  , we have

, we have

for any finite-dimensional representation  of

of  with character

with character  , provided the latter does not vanish identically on

, provided the latter does not vanish identically on  (this may happen, e.g., for the regular representation of

(this may happen, e.g., for the regular representation of  ). This was used by Burnside (and still appears in many books) in order to prove that if an irreducible representation

). This was used by Burnside (and still appears in many books) in order to prove that if an irreducible representation  of a finite group has degree at least

of a finite group has degree at least  , its character must be zero on some elements of the group. (The cyclic groups

, its character must be zero on some elements of the group. (The cyclic groups  used are those generated by non-trivial elements of the group, and the representations are the restrictions of

used are those generated by non-trivial elements of the group, and the representations are the restrictions of  to those cyclic groups; thus it is an interesting application of reducible representations of abelian groups to irreducible representations of non-abelian ones… the lion and the mouse come to mind.)

to those cyclic groups; thus it is an interesting application of reducible representations of abelian groups to irreducible representations of non-abelian ones… the lion and the mouse come to mind.)

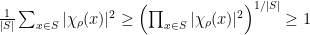

This inequality can not be considered hard: it is dispatched in two lines invoking Galois theory to argue that

is a (non-negative) integer, and the arithmetic-geometric inequality to deduce that

unless this product is zero.

However, if we view this as a property of representations of a finite cyclic group, one (or, at least, I) can’t help wonder whether there is a “direct” proof, which only involves the formal properties of these representations, and does not refer to Galois theory. This is what I was trying to understand while basking in the italian spring and gardens. As it turns out, there is is in fact quite a beautiful argument, which is undoubtedly too complicated to seriously replace the Galois-theoretic one, but is directly related to very interesting facts which I didn’t know before — I therefore consider well-spent the time spent thinking about this inequalitet. (Philological query: what is the diminutive of “inequality”? or of “formula”?)

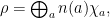

The idea is that a representation  of

of  is a direct sum

is a direct sum

where  runs over

runs over  , and

, and  is the character

is the character

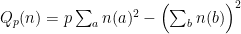

for some integral multiplicities  . Hence the left-hand side of Burnside’s inequality, namely

. Hence the left-hand side of Burnside’s inequality, namely

can be seen as a quadratic form in  integral variables, and the question we ask is: what is the minimal non-zero value it can take? (Note that the example of the regular representation shows that this quadratic form, though obviously non-negative, is not definite positive.)

integral variables, and the question we ask is: what is the minimal non-zero value it can take? (Note that the example of the regular representation shows that this quadratic form, though obviously non-negative, is not definite positive.)

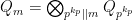

Now the funny part of the story is that this quadratic form, say  , is naturally a tensor product

, is naturally a tensor product

of the corresponding quadratic forms arising from the primary factors of  . Hence we have a problem about a multiplicatively defined quadratic form, and the answer (given by Burnside) is rhe Euler function

. Hence we have a problem about a multiplicatively defined quadratic form, and the answer (given by Burnside) is rhe Euler function  , which is also multiplicative; should it not then feel natural to treat the case of

, which is also multiplicative; should it not then feel natural to treat the case of  for some prime

for some prime  , and claim that the general case follows by multiplicativity?

, and claim that the general case follows by multiplicativity?

Alas, a second’s thought shows that it is by no means clear that the minimum of a tensor product of (non-negative, integral) quadratic forms should be the product of the minima of the factors! Denoting by  the minimum of

the minimum of  (among non-zero values), we certainly have

(among non-zero values), we certainly have

but the converse inequality should immediately feel doubful when the forms are not diagonalized. And indeed, in general, this is not true! I found examples in the book of Milnor and Husemoller on bilinear forms (which I had not looked at for a long time, and I am very happy to have been motivated to look at it again!); they are attributed to Steinberg, through a result of Conway and Thompson, itself based on the famous Siegel formula for representation numbers of quadratic forms…

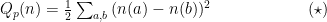

However, despite this fact about general forms, it turns out that the quadratic forms  have the property that

have the property that

for all other quadratic forms  (always non-negative integral). This I found explained by Kitaoka. Here the nice thing is that it depends on writing

(always non-negative integral). This I found explained by Kitaoka. Here the nice thing is that it depends on writing  as (essentially) a variance

as (essentially) a variance

of the coefficients  , and using the alternate formula

, and using the alternate formula

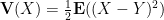

which corresponds, in probability, to the formula

for the variance of a random variable  , using an independent “copy”

, using an independent “copy”  of

of  (i.e.,

(i.e.,  is has the same probability distribution as

is has the same probability distribution as  , but is independent.) This probabilistic formula, I have to admit, I didn’t know — or had forgotten –, though it is very useful here! Indeed, the reader may try to prove directly that

, but is independent.) This probabilistic formula, I have to admit, I didn’t know — or had forgotten –, though it is very useful here! Indeed, the reader may try to prove directly that  unless it is

unless it is  , using any of these formulas for

, using any of these formulas for  ; I succeeded with the other formula

; I succeeded with the other formula

but the argument was much uglier than the one with  above! (It is also clearer from the latter that

above! (It is also clearer from the latter that  takes integral values for integral arguments, despite the

takes integral values for integral arguments, despite the  which crop up here and there…)

which crop up here and there…)

For more details, I’ve written this up in a short note that I just added to the relevant page.

, the integers

such that, when

is written in base

, the integers obtained by all cyclic permutation of the digits are in arithmetic progression.

; the cyclic permutations yield the additional integers

and

; and — lo and behold — we have indeed

, wich can be permuted with the others, so that, for instance,

, with companions

and

, is also a solution.)

; with — in order — the progression

(which is also the smallest of the 6 integers.)

. The original problème d’agrégation asked for cycles of lengths 3 and 6 in base 10 and Cartan finds 3 cycles of length 6 and 6 of length 3. I wonder how many students managed to solve this question…