In no particular order, and with no relevance whatsoever to the beginning of the year, here are three mathematical facts I learnt in recent months which might belong to the “I should have known this” category:

(1) Which finite fields  have the property that there is a “square root” homomorphism

have the property that there is a “square root” homomorphism

i.e., a group homomorphism such that  for all non-zero squares

for all non-zero squares  in

in  ?

?

The answer is that such an  exists if and only if either

exists if and only if either  or

or  is not a square in

is not a square in  (so, for

(so, for  , this means that

, this means that  ).

).

The proof of this is an elementary exercise. In particular, the necessity of the condition, for  odd, is just the same argument that works for the complex numbers: if

odd, is just the same argument that works for the complex numbers: if  exists and

exists and  is a square, then we have

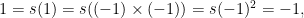

is a square, then we have

which is a contradiction (note that  only exists because of the assumption that

only exists because of the assumption that  is a square).

is a square).

The question, and the similarity with the real and complex cases, immediately suggests the question of determining (if possible) which other fields admit a square-root homomorphism. And, lo and behold, the first Google search reveals a nice 2012 paper by Waterhouse in the American Math. Monthly that shows that the answer is the same: if  is a field of characteristic different from

is a field of characteristic different from  , then

, then  admits a homomorphism

admits a homomorphism

with  , if and only if

, if and only if  is not a square in

is not a square in  .

.

(The argument for sufficiency is not very hard: one first checks that it is enough to find a subgroup  of

of  such that the homomorphism

such that the homomorphism

given by  is an isomorphism; viewing

is an isomorphism; viewing  as a vector space over

as a vector space over  , such a subgroup

, such a subgroup  is obtained as the pre-image in

is obtained as the pre-image in  of a complementary subspace to the line generated by

of a complementary subspace to the line generated by  , which is a one-dimensional space because $-1$ is assumed to not be a square.)

, which is a one-dimensional space because $-1$ is assumed to not be a square.)

It seems unlikely that such a basic facts would not have been stated before 2012, but Waterhouse gives no previous reference (and I don’t know any myself!)

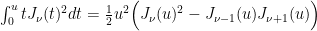

(2) While reviewing the Polymath8 paper, I learnt the following identity of Lommel for Bessel functions (see page 135 of Watson’s treatise:

where  is the Bessel function of the first kind. This is used to find the optimal weight in the original Goldston-Pintz-Yıldırım argument (a computation first done by B. Conrey, though it was apparently unpublished until a recent paper of Farkas, Pintz and Révész.)

is the Bessel function of the first kind. This is used to find the optimal weight in the original Goldston-Pintz-Yıldırım argument (a computation first done by B. Conrey, though it was apparently unpublished until a recent paper of Farkas, Pintz and Révész.)

There are rather few “exact” indefinite integrals of functions obtained from Bessel functions or related functions which are known, and again I should probably have heard of this result before. What could be an analogue for Kloosterman sums?

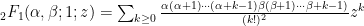

(3) In my recent paper with G. Ricotta (extending to automorphic forms on all  the type of central limit theorem found previously in a joint paper with É. Fouvry, S. Ganguly and Ph. Michel for Hecke eigenvalues of classical modular forms in arithmetic progressions), we use the identity

the type of central limit theorem found previously in a joint paper with É. Fouvry, S. Ganguly and Ph. Michel for Hecke eigenvalues of classical modular forms in arithmetic progressions), we use the identity

where  is a fixed integer and

is a fixed integer and

This is probably well-known, but we didn’t know it before. Our process in finding and checking this formula is certainly rather typical: small values of  were computed by hand (or using a computer algebra system), leading quickly to a general conjecture, namely the identity above. At least Mathematica can in fact check that this is correct (in the sense of evaluating the left-hand side to a form obviously equivalent to the right-hand side), but as usual it gives no clue as to why this is true (and in particular, how difficult or deep the result is!) However, a bit of looking around and guessing that this had to do with hypergeometric functions (because

were computed by hand (or using a computer algebra system), leading quickly to a general conjecture, namely the identity above. At least Mathematica can in fact check that this is correct (in the sense of evaluating the left-hand side to a form obviously equivalent to the right-hand side), but as usual it gives no clue as to why this is true (and in particular, how difficult or deep the result is!) However, a bit of looking around and guessing that this had to do with hypergeometric functions (because  is close to a Legendre polynomial, which is a special case of a hypergeometric function) reveal that, in fact, we have to deal with about the simplest identity for hypergeometric functions, going back to Euler: precisely, the formula is identical with the transformation

is close to a Legendre polynomial, which is a special case of a hypergeometric function) reveal that, in fact, we have to deal with about the simplest identity for hypergeometric functions, going back to Euler: precisely, the formula is identical with the transformation

where

is (a special case of) the Gauss hypergeometric function.

![[Scuola Normale Superiore]](http://blogs.ethz.ch/kowalski/files/2013/11/DSCN3040-300x224.jpg)

![[Pisa]](http://blogs.ethz.ch/kowalski/files/2013/11/DSCN3089-e1385293847760-224x300.jpg)