How smart grids will change the way architects have to design buildings

On 30.11.2020 by Christoph WaibelBy Dr. Christoph Waibel

Christoph Waibel is a Postdoc at the Chair of Architecture and Building Systems at ETH Zurich and is involved in the development of “Hive”, an ETH Innovedum funded teaching tool for energy-responsive architectural design. Christoph’s research interests are in developing and utilizing models and algorithms for an informed decision making process of energy efficient buildings and neighborhoods.

In order to efficiently integrate intermittent renewable energy into our grids, we need to change the role that buildings play in a city. Instead of being mere consumers, they need to become a swarm of smart prosumers capable of stabilizing the grid. This calls for a new way how architects should design buildings, leading to the next era of architecture: “Energy Responsivism”.

Currently, most buildings are mere consumers. They need energy for utilities and room climatisation, and they simply take this energy from the grid. They use whatever they need, whenever they need it. But if we are to efficiently integrate more of the highly intermittent and fluctuating solar and wind energy into our grid, it suggests that we reform the role buildings play. This, in turn, calls for a new way architects should design buildings.

From buildings as individuals to buildings as team players

In an ideal future, buildings will evolve from consumers to prosumers: Instead of a one-directed energy flow into the building, energy will dynamically flow both ways out of and into the grid. This is made possible by equipping buildings with photovoltaic panels and batteries to store and feed-in self-generated clean electricity. Furthermore, in conjunction with smart controls, thermal mass of the buildings will be utilized as a dynamic and responsive grid stabilizer without compromising on the comfort of the occupants . This way, buildings can cover much of their required energy themselves, and even significantly contribute towards a stable, clean, and efficient grid.

Smart grids will change architectural design

Historically, innovations and changes of a technical (e.g., the introduction of materials such as steel and concrete) or societal nature (e.g., media facades at the Piccadilly Circus displaying consumerism) are usually also reflected in a transformation of contemporary architectural style (Fig. 1). Consequently, it can be expected that a transformation in energy infrastructure (smart grids) will result in a new architectural style of energy responsive buildings. From Postmodernism, Deconstructivism, Parametricism, finally to Energy Responsivism as a new era in architecture?

While most architectural styles essentially expressed individualistic solitaires (the particular building was the center of attention), prosumer buildings in the era of Energy Responsivism have to extend their system boundaries, where buildings are understood as part of collaborating networks. It is apparent that this requires a fundamentally different approach towards how architects design buildings, accompanied by a new set of skills for architects to master. It includes tools for energy-related topics that were traditionally attributed to engineering disciplines, such as building energy demand assessment or PV electricity generation calculations.

Fig. 1. Architectural examples displaying their respective Zeitgeist.

Top left: Crystal palace by Joseph Paxton. (Image source: www.wikipedia.com)

Top right: Piccadilly Circus in London. (Image source: www.wikipedia.com)

Bottom: The “Nest” research building as pioneer of “Energy Responsivism”? (Image source: https://strom-online.ch/das-nest-der-empa/)

Smart buildings – smart architects?

An architect these days has to deal with a multitude of technical aspects that extend beyond what is traditionally understood as architectural design: smart meters and smart grids, renewable energy such as building integrated photovoltaic (“But that ruins the aesthetics!”), building controls (letting a computer decide when to lower the sunscreens), demand response (“The dishwasher might start sometime between now and the next 12 hours, thank you for your patience”), heat pumps and storages (“those ugly things in the basement”), etc.

Related topics around sector coupling, grid integration and demand side management — crucial keystones in the urban energy transition — are still in the exploration and experimentation phase. Highly specialized experts with backgrounds in energy, economics or computer science are conducting complex, ongoing research. However, given the expected long life time of buildings, architects should already now consider these recent technical and scientific insights when designing new or refurbishing existing buildings; they must be compatible with future smart grids, if they are to contribute to overcoming global environmental challenges. This means that architects have to change their trained habits and adapt to a new way of designing buildings.

Being able to design energy responsive buildings without a PhD

So far, I have argued that the energy transition will also lead to a new style of architecture because of the fundamentally different role buildings will play. Formally, this might be expressed by various design interventions. For example, energy active facades and building components; different choices of materiality because of the impact this has on thermal latency; or by having more functional diversity within neighborhoods and buildings, as this is known to facilitate operational flexibility of an energy system.

These interventions are technically complex and currently, architectural training does not demand that students also be expert physicists, engineers, and computer scientists simultaneously — nor should it. If we want architects to design energy responsive buildings that contribute to a future with sustainable energy infrastructure, they will need an entirely new set of tools that enable them to extract technical information and synthesize it into their designs. It should be a matter of course in designing and retrofitting future buildings that the energy demand of design alternatives is assessed, that the electricity generation potential of building-integrated PV is considered, and that the load-shifting ability of a building is well understood.

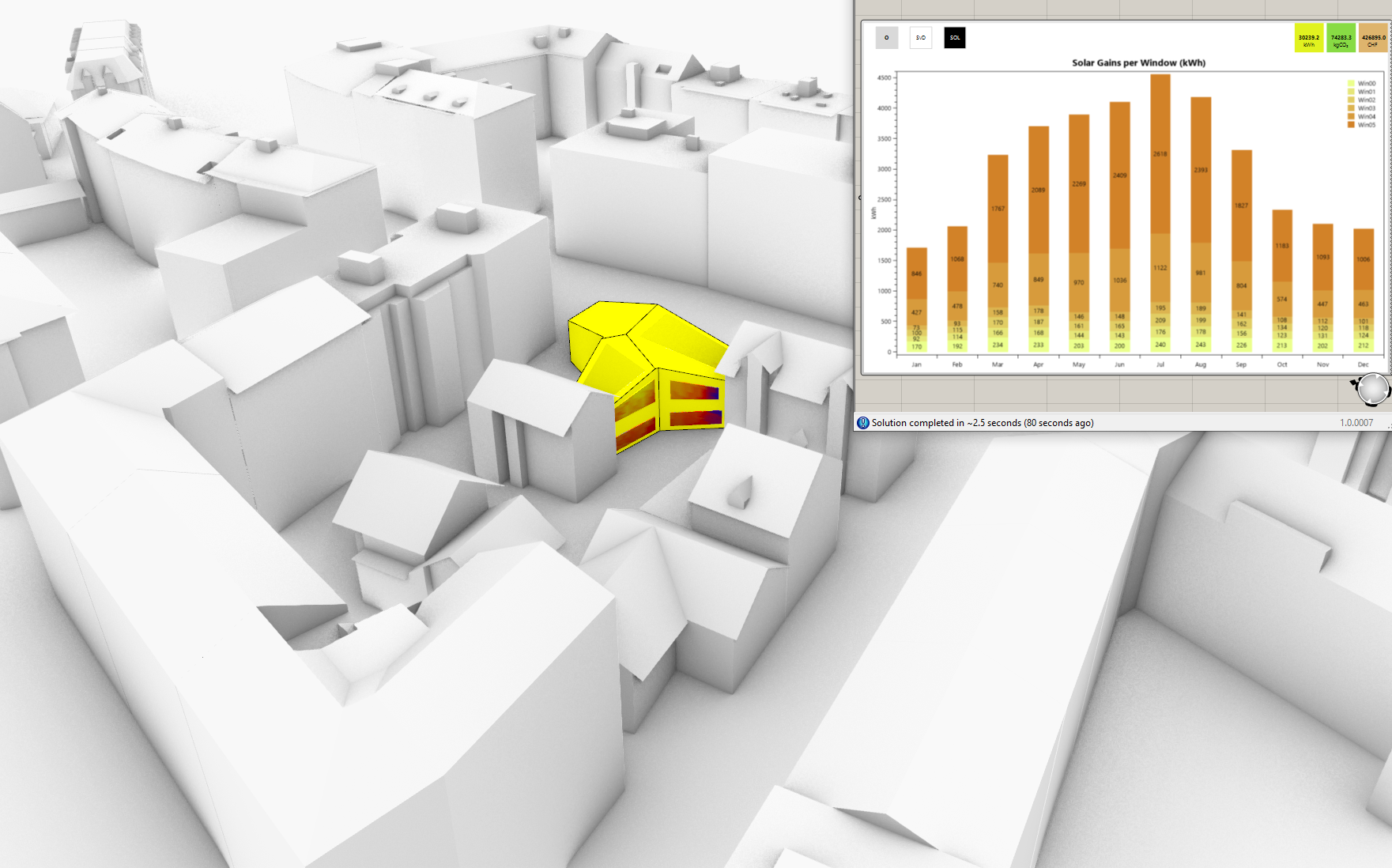

Fig. 2. The “Hive” tool for energy responsive architectural design in teaching.

For architects, therefore, tools that allow them to intuitively and effectively evaluate the performance of design alternatives will become indispensable. One step in this direction is “Hive”, an architecture-focused performance evaluation tool developed at the Chair of Architecture and Building Systems at ETH Zurich, and funded by an ETH Innovedum grant. Hive is an open source plug-in for the CAD program Rhinoceros 3D and its visual programming platform Grasshopper. It includes fast calculation models that are appropriate at an early design stage and hence enables architecture students to get sensitized for energy-related topics (Fig. 2).

Considering an ever increasing technological complexity of smart buildings, are architects still the right people to design them? Yes, they are! But instead of overloading their university curriculum with more engineering, physics, and computer science, they need the right tools that provide them with instant performance feedback. Such performance evaluation tools would allow them to intuitively understand cause-and-effect relations necessary for making informed decisions. Furthermore, such tools can serve as a bridge of communication between expert domains and thus foster interdisciplinary collaboration. This way, architects can focus on the creativity and continue to do what they do best: design great, energy responsive buildings.

Cover photo by District Energy In Cities: Unlocking the Potential of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy. United Nations Environment Programme (2015)

Keep up with the Energy Blog @ ETH Zurich on Twitter @eth_energy_blog.

Suggested citation: By Waibel, Christoph. “How smart grids will change the way architects have to design buildings”, Energy Blog @ ETH Zurich, ETH Zurich, December 4th, 2020, https://blogs.ethz.ch/energy/smart-grids/

Hey Christoph,

I really enjoyed reading your insightful post. I would have two questions: First, how do does Energy Responsivism as the new era of architecture impact interventions in existing buildings, given also that these form a big part of the building and urban energy challenge? Will there be new design dimensions involved in retrofitting or will it mostly be a technical problem to solve? Second, you mention that architects should not be physicists, engineers and computer scientists simultaneously and rightly so. With advanced tools like Hive, do you think that there is still a role that interdisciplinary teams can and need to play in building design or do they become less important?

Cheers,

George

Hi George,

thanks for your comments, you mention some important points here!

When it comes to retrofitting, there is certainly less degree of freedom in design as compared to new constructions. But also in refurbished buildings we can observe distinct features of energy responsivism: increasing fabric insulation, changing heat emission systems from high temperature radiators to underfloor heating, integrating photovoltaic (BIPV) on roof and facades, etc. From an aesthetic standpoint there has been much criticism especially about adding external insulation and BIPV, so we can see that architecture is still experimenting with energy-related design interventions.

Regarding your 2nd point, I believe the right tools will ease interdisciplinary collaboration and will make diverse teams even more important and effective, because it allows them to get a common understanding of the subject. Specialists in different domains will still be required, and we need to make sure they understand each other.

Regards,

Christoph

Hey Christoph,

Thanks for your interesting post. I could identify myself in many points you mention about architecture and new sustainable technologies. I myself as an architect recognize the increasing demands architects are facing while designing a building. Already in the phase of a competition the required technical competences are increasing continously. Not only the urban suitability, the functuality, architectural expression and suitable construction needs to be considered. But in the last years building services including the different MINERGIE standards, photovoltaic or greening systems for facades or roofs are required as in integral part of the design. I would appreciate new tools which can support the design process of an architect already in the beginning where decisions need to be taken fast. Without abandoning the professional exchange with experts in the second phase.

Best regards,

Anna

Dear Christoph,

you pick up architecture in your one hand and energy engineering in your other hand, you smash them together, and out comes… Energy Responsivism or a new era in architecture. Tada!

Coming from a power engineering background, I believe that power engineers have allowed technologies (esp. solar PV, battery storage, heat pumps, electric vehicles, and electrolyzers) to mold and in some ways limit their thinking to the dimensions power-to-mobility, power-to-heat, and most lately (probably the next publication wave) power-to-molecules. Notice the lack of power-to-buildings (or buildings-to-power?). Indeed the 2nd IRENA Innovation Landscape Report (to be released in Q4 2021) may well address all innovations for end-sector electrification, which drive Energy Responsivism, without addressing buildings. Try to search “buildings” in the 1st IRENA Innovation Landscape Report (https://www.irena.org/-/media/Files/IRENA/Agency/Publication/2019/Feb/IRENA_Innovation_Landscape_2019_report.pdf). Where does the electricity sector’s indifference towards buildings come from?

First, in the old centralized and regulated electricity system, buildings exerted only a minor impact on the distribution and transmission system; and their impact on balancing and generation was mostly stochastic. Clearly, decentralization has changed the playing field, and buildings take a much more prominent role now as the place where a lot of energy technologies concentrate. Second, I believe power engineers still predominantly look at buildings as merely the sum of the deployed energy technologies. If architects nowadays influence which energy technologies are deployed and how these technologies are deployed, power engineers can no longer ignore architects and buildings as drivers of the power system transformation. I wonder whether the emergence of Energy Responsivism in architecture calls for the emergence of Buildings Responsivism in power engineering. While power engineers have certainly been reactive to changes in the electricity system that originate from buildings, the notion that buildings as a non-energy-technol0gy “drive” the power sector and its transformation is rather novel.

Regards,

Stefan