Coal phase-out: Conflictive but unavoidable

On 12.06.2020 by jmarkard@ethz.chBy Jochen Markard

Jochen Markard is a Senior Scientist in the Group for Sustainability and Technology (SusTec) at ETH Zurich. The study on the UK was conducted together with Karoliina Isoaho from the University of Helsinki. The ideas around sustainability transition policies were developed together with Daniel Rosenbloom from the University of Toronto.

Phasing-out carbon-intensive technologies and business models is a key element for deep decarbonization. Coal is a prime candidate for phase-out and we cannot waste any time. However, every industry decline creates conflicts. Overcoming these conflicts is the key to success.

Renewable energies are often on the top of our heads when we think about the energy transition. We typically look at innovation, new technologies, or new business opportunities. However, industrial decline and technology phase-out are also key elements for our ambition to create low-carbon societies. Decline is the flipside of innovation. Less shiny, conflictive, painful but unavoidable.

Coal phase-out as a key element in the energy transition

As governments around the world devise policies to tackle climate change, coal-fired power generation is often in the focus. Coal not only comes with high CO2 emissions but also contributes to (local) air pollution. Numerous countries including, for example, the UK, Finland, Canada, or Germany have meanwhile formulated policies to phase-out unabated coal-based power generation, and 33 national governments have joined the “Powering Past Coal Alliance”.

A particularly interesting case is the UK. 40 years back, coal contributed to more than 70% of the country’s electricity generation and domestic coal mining was a central source of employment in many regions. Last year, coal was down to around 2% and many expect that the few remaining power plants will be closed before 2025 (which is the official end date of the 2015 government pledge for coal phase-out). So, what happened?

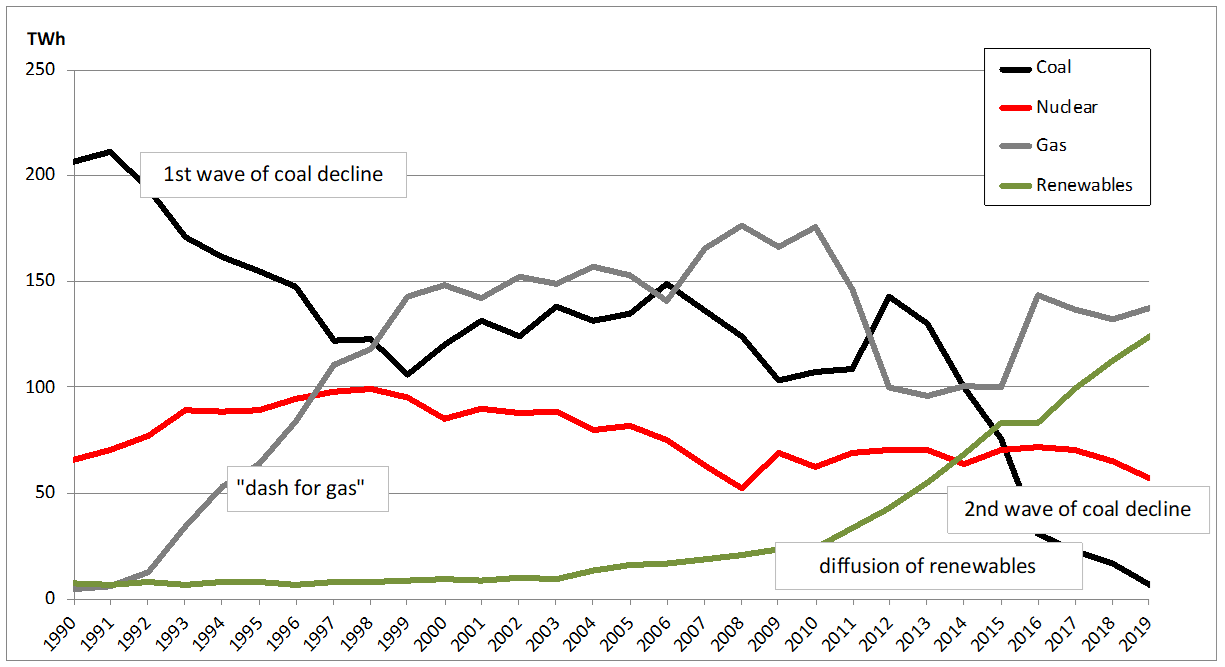

Figure 1: Changes in UK power generation from 1990 to 2019

A scene in two-acts

The UK coal industry declined in two waves (Figure 1). The first happened in the 1990s when electricity markets were liberalized and subsidies for coal mining cut in the wake of Thatcher’s neoliberal policy agenda. The “dash for gas” drove a major part of the country’s coal power plants out of business and the share of coal in the electricity declined to 32% in 2000. The second wave happened just recently. From 2014 to 2019, most of the remaining coal power plants were shut down.

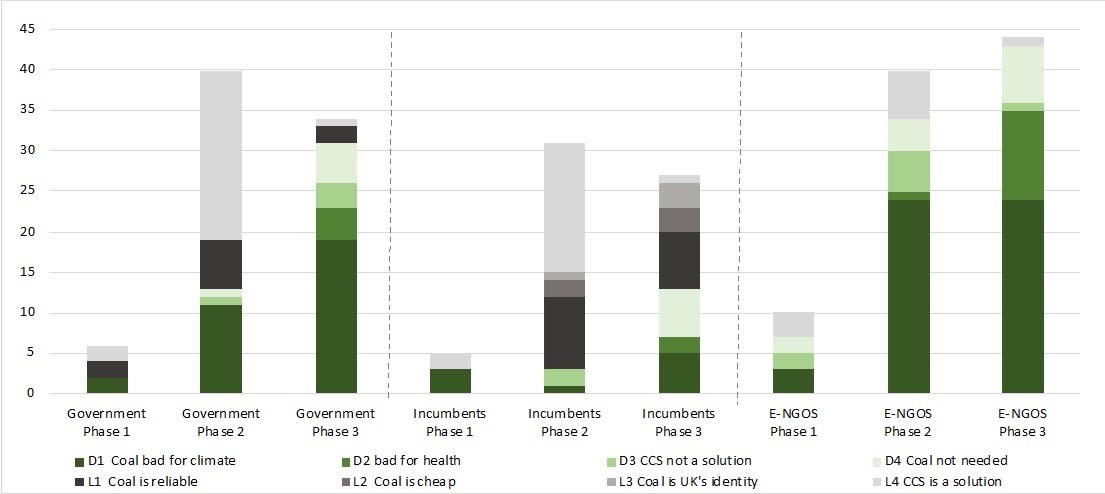

In a recent study, we tracked statements of different groups of actors in the UK by analysing articles on coal and coal phase-out in The Guardian. For many years, the British government and coal industry incumbents tried to defend coal against increasing criticism from environmental NGOs (E-NGOs) and health experts (Figure 2). The main narrative in favor of coal was based on carbon capture and storage technology (CCS) as a potential solution. This hope never materialized, though, and from around 2013 onwards, the resistance by the government and incumbents weakened. The phase-out pledge in 2015 finally sealed the fate of coal.

Figure 2: Arguments in favor (grey) and against coal (green) by different actor groups. Phase 1: 2000-07, Phase 2: 2008-12, Phase 3: 2013-17

The public discourse was not the only factor that contributed to coal’s decline in the UK. The 2008 Climate Change Act, the introduction of a carbon price floor in 2013, and various renewable energy policies were important as well. Also, the UK had a pretty old fleet of coal power plants many of which did not comply with EU clean air regulation any more. So, in the end, coal phase-out was less conflictive than anticipated: the jobs in mining were long gone and most power plants were at the end of their lifespan anyway.

Lessons for other phase-outs

The successful coal phase-out in the UK holds several lessons for other countries. First, transitions are contested. So, prepare for resistance, conflicts and conflict resolution. All existing industries have strong ties with political decision-makers and are supported by influential constituencies, most of which perceive the transformation as a threat. In the case of coal, labour unions and social democratic parties often form ‘unholy’ alliances against climate change. Second, and due to this resistance, it is important to develop alternatives, e.g., through innovation and deployment policies. In the UK, these alternatives were renewables and natural gas, which, of course, can only be an interim solution and comes with the risk of another fossil fuel lock-in. It is also important to support new perspectives for those communities and regions who feel left behind. Third, transitions require policies that put pressure on carbon-intensive industries. These may include effective carbon pricing schemes as well as specific phase-out policies. Fourth, transitions often take decades, which is why they require long-term policy guidance. In the UK, this guidance was largely missing and the phase-out pledge by the government only came at a time when the decline was already happening.

Finally, it is important to note that there is no silver bullet for coal phase-out or climate policy more broadly. We often hear that carbon pricing is the key to climate policy. I disagree. Phasing out coal is a policy strategy that can be very effective: it targets a major source of emissions and an industry that cannot escape to unregulated places. Moreover, it focuses on a sector where affordable solutions are available. Of course, coal phase-out is only one policy strategy. Many more will be needed. In fact, to address climate change, we need a broad range of policies that reduce emissions quickly. These policies have to be tailored to the specific context and should be designed with some inherent flexibility so that they can be adapted as the transition progresses.

Cover photo acquired under CC from Flickr

Sources

[1] Isoaho, K., Markard, J., in press. The politics of technology decline: Discursive struggles over coal phase-out in the UK. Review of Policy Research.

[2] Turnheim, B., Geels, F.W., 2012. Regime destabilisation as the flipside of energy transitions: Lessons from the history of the British coal industry (1913-1997). Energy Policy 50, 35-49.

[3] Natural gas, of course, can only be an interim solution and comes with the risk of another fossil fuel lock-in.

[4] Johnstone, P., Hielscher, S., 2017. Phasing out coal, sustaining coal communities? Living with technological decline in sustainability pathways. The Extractive Industries and Society 4, 457-461.

[5] For example, countries differ in terms of geography, energy mix, infrastructure, industry structure, political system and policy culture, societal preferences, level of ambition etc. These differences are best served by combinations of policies (so-called ‘policy mixes’). See: Kern, F., Rogge, K.S., Howlett, M., 2019. Policy mixes for sustainability transitions: New approaches and insights through bridging innovation and policy studies. Research Policy 48, 103832.

[6] Rosenbloom, D., Markard, J., Geels, F.W., Fuenfschilling, L., 2020. Why carbon pricing is not sufficient to mitigate climate change — and how “sustainability transition policy” can help. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117, 8664-8668.

Keep up with the Energy Blog @ ETH Zurich on Twitter @eth_energy_blog.

Suggested citation: Markard, Jochen. “Coal phase-out: Conflictive but unavoidable“, Energy Blog, ETH Zurich, June 12, 2020, https://blogs.ethz.ch/energy/coal-phase-out/

If you are part of ETH Zurich, we invite you to contribute with your findings and your opinions to make this space a dynamic and relevant outlet for energy insights and debates. Find out how you can contribute and contact the editorial team here to pitch an article idea!

I think the author ignores the first act in this play: the collapse of UK domestic coal production (mining that is), which started in the 60ies. impressive charts here: https://ourworldindata.org/death-uk-coal

Most jobs in coal are not in power plants but in mining. And jobs are a core political currency. Domesitc coal production is btw still huge in other countries (where the UK lessons might therefore only be of partial value), think: Poland, Australia, South Africa.

just saying…

Finally, a comment! I was already suspecting everybody on vacation…

I fully agree, domestic jobs in mining are a major policy issue when it comes to coal decline. That’s why it is important to create new jobs around technologies of the future.

Unfortunately, established – and often influential – unions may fight against sustainable transformation in the name of job protection – in energy but also in other industries such as cars, steel etc.

But where is the perspective in protecting the jobs of the past? The challenge is to help create the jobs of the future. For example, see this graph on Germany by Pau-Yu Oei comparing jobs in coal vs. renewables.

Developed countries should indeed aim for rapid and deep decarbonisation. Deep carbonisation is needed globally, but developed countries must lead the way and provide a model and template for developing countries to emulate.

The fact that Great Britain was able to do without coal so quickly and will soon be able to do without natural gas has to do with the fact that Great Britain is relying on a strong expansion of wind power (especially off-shore) as well as nuclear energy. With the help of nuclear energy, Great Britain can cope with temporary wind chill without the need for massive electricity imports.

If, on the other hand, Switzerland wants to do without nuclear energy, it will probably not be able to do so without gas-fired power plants, because how else can it generate enough electricity for the winter with solar and wind power alone? The ETH report “Energiezukunft Schweiz” ( https://ethz.ch/content/dam/ethz/special-interest/mavt/energy-technology/aerothermochemistry-dam/documents/160218ib_Energiezukunft_Schweiz.pdf ), which predicts that Switzerland will be mainly supplied with solar energy in the future, sees the need for gas power plants as soon as the nuclear power plants are shut down.

It is a misconception that nuclear and wind are complementary. Nuclear is no help in copig with “temporay wind chill” bc nuclear is not flexible. Unlike gas, it must run constantly. Due to low demand –> Covid-19, the UK has currently, and temporarily, reduced the output of Sizewell B, one of its nuclear power stations. Link.

Compared to the UK, Switzerland is in the comfortable situation of having hydropower with short term and seasonal storage to complement variable renewables. Plus transmission interconnectors with all our neighbors.

Gas and wind/sun fit indeed better together then nuclear and win/sun. But that Sizewell B reduced its output during the Covid-19 pandemic shows its potential for a certain flexibility.

I believe the consensus for Switzerlands energy situation is that a combination of hydro and solar energy would leave a winter electricity gap (quote: “According to our study, we would be 22 terawatt hours short of electricity in the winter half-year”, explains researcher Martin Rüdisüli from Empa’s Urban Energy Systems Department in the NZZ am Sonntag”).

This gap could be closed with gas power or electricity import as is already done today. But it is widely believed that neighbouring countries in the near future will also produce too less electricity during winter.

Natural gas power plants could therefore become necessary.