Tackling the energy crisis in Europe is a common effort

On 23.11.2022 by Jacob MannhardtBy Jacob Mannhardt

Jacob Mannhardt is a first-year PhD candidate at the Reliability and Risk Engineering Lab at ETH Zürich. His main research focus is on transition pathways towards the decarbonization of the European energy system, with a special focus on the modeling of investment decision-making.

The secret to getting through the energy crisis is that everyone in Europe does their part. And a bit of luck. In this blogpost, we highlight some preliminary results from our investigation of the gas shortage in Europe – because winter is here but Russian gas is not. We model the optimal response to the gas crisis to outline a potential strategy for European countries to get through this daunting situation.

Europe is in the tight grip of the worst energy crisis in decades. Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the resulting sanctions by European countries, Russia reduced its gas exports to Europe, previously supplying 40% of the continent’s demand. This immense volume is now all but gone and the current political situation makes a quick return in the near future unlikely. As winter looms, the fear of a gas shortage has spurred a drastic hike in energy prices, leaving most European countries and citizens worried about how to get safely through the winter.

Optimizing the response to the gas shortage

In an effort to better understand what Europe can do to survive the winter, we at the Reliability and Risk Engineering Lab analyzed the impact of a total Russian gas disruption to understand how a gas shortage could be best compensated in Europe in the coming winter. In our analysis, we modeled the struggle to supply and consume gas in Europe, formulating it as a cost-minimization optimization problem. The model selects the optimal pathway to substitute the missing Russian gas. We find three main compensation strategies along the gas supply chain that are deployed in combination:

- Additional gas imports from other sources than Russia

- A shift of electricity and heat generation to non-gas-fired technologies

- Reduction of the final energy demands electricity, heat, and industrial gas

Our preliminary results suggest that most countries will need to reduce some of their electricity, heat, and industrial gas demand. However, the additional gas imports and the shift to other technologies can relieve most of the stress if all countries in Europe support each other in this fight. Energy savings as a precautionary measure paired with a mild winter are the most effective tool to tackle the energy crisis. In this blogpost, we comment only on the preliminary results of the third strategic action to reduce the final energy demands in various winter scenarios; in our upcoming study, we investigate all three compensation strategies in combination.

Public effort and a tiny bit of luck

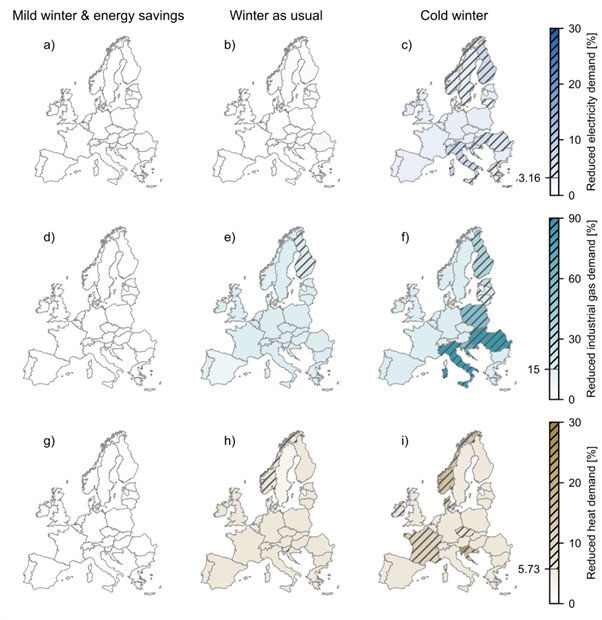

The energy crisis is a struggle to meet Europe’s final energy demands. This is because gas is required for electricity generation, heating, and as an input in the industrial sector. Reducing energy demand would be a necessary measure, if the gas available to meet the needs of these three sectors in a country is insufficient. The severity of the coming winter will determine our ability to get through it. In Figure 1, we map out three possible winter outcomes in Europe:

- A usual winter, comparable to 2021 (center column)

- A mild winter with additional energy savings as a precautionary measure (lower heat and electricity demand, left column)

- A cold winter (higher heat demand, right column)

Comparisons of country-specific optimal requirements to reduce the energy demands under the different winter outcomes are depicted in Figure 1 for the electricity, heat, and industrial gas sectors. In our model, the first step to reducing the final energy demands is voluntary with minor strain to citizens: they may choose to adjust their thermostats, shops may turn off their window lighting, and the industry may use other feedstocks in production. For each sector, we identified a threshold above which voluntary demand reductions are not sufficient anymore. In the event that this threshold is surpassed, the government might need to intervene and mandate that citizens and industrial consumers reduce their consumption.

In a usual winter (Fig. 1b,e,h), voluntary demand reductions are generally sufficient for most countries. On the other hand, a cold winter (Fig. 1c,f,i) with higher heat demand puts a strain on all sectors of the energy system. As a consequence, more countries would need to significantly reduce energy demand: countries like Italy which strongly depend on gas for electricity generation would be severely hit by the colder winter. In the worst case, those countries dependent on gas would need to cut up to almost 90% of their industrial gas consumption to keep the energy system afloat. We already see many Eastern European countries strongly reducing their gas consumption. Being lucky with a mild winter reduces the heat demand and relieves the stress of the energy crisis. As a precautionary measure, further proactive efforts to reduce electricity use would minimize any additional demand reduction requirements anywhere in Europe as observed in Figure 1a,d,g. Preemptive energy savings are the most effective tool to mitigate the impact of the gas shortage and will likely determine the extent to which we have to rely on luck.

Figure 1: Schematic showing required demand reductions for Europe without Russian gas in a mild winter with high energy savings, a usual winter, and a cold winter scenario. Reduction of electricity, industrial gas, and heat demand. Darker shaded countries reflect higher demand reduction requirements over the next year from November 2022 until October 2023. Countries with involuntarily reduced demand are hatched.

Gas infrastructure bottlenecks are a matter of concern

A key observation from Figure 1 is that while most Western European countries can get through the crisis in cold winter without great concessions, the countries in the East like Hungary and Croatia struggle significantly. Fatih Birol, executive director of the International Energy Agency, called the upcoming winter “a historic test of European solidarity – one it cannot afford to fail“. The Northeastern countries, which previously imported most of the European gas from Russia and transported it further into the continent, are now in need of gas imports from other European countries. We find that this situation is problematic because the gas infrastructure was not designed for large flows from the West to the East. Our preliminary results suggest that the European gas network might become overloaded because of these new flows from West to East. And as a result, this makes it more difficult to supply the Eastern countries with gas.

Supporting the countries in the East is vital

The impact of the gas shortage can be eased if we collectively lower our energy consumption as a precautionary measure. If we then further experience a mild winter, getting through the energy crisis is manageable. We recommend incentivizing citizens to follow energy-saving measures such as thermostat adjustment or lowered electricity consumption. The industrial sector can often switch to other fuels or reduce their production but will need compensation to do so.

We call on European policymakers to consider the barriers associated with the internal bottlenecks of the gas network and transport gas to the Eastern countries in need. Europe must ensure to share the gas among all countries, even if this means reducing some of the domestic energy demand in all countries. Collaboration in the energy crisis is the least harmful way to get through the winter in Europe.

Cover photo by Kwon Junho on Unsplash

Keep up with the Energy Blog @ ETH Zurich on Twitter @eth_energy_blog.

Suggested citation: Mannhardt, Jacob. “Tackling the energy crisis in Europe is a common effort”, Energy Blog @ ETH Zurich, ETH Zurich, November 23, 2022, https://blogs.ethz.ch/energy/europe-gas-shortage/

If you are part of ETH Zurich, we invite you to contribute with your findings and your opinions to make this space a dynamic and relevant outlet for energy insights and debates. Find out how you can contribute and contact the editorial team here to pitch an article idea!

The “energy crisis 2022/23 in Europe” is in the first place self-made: Hadn’t we spent nearly a half century in deep sleep concerning the transition from non-renewable to 100% renewable energy resources, then Putin’s act of madness would not have released a European energy crisis as big as a tsunami, but only as small as a soft water ripple (if at all). So, let’s not pity ourselves, let’s rather pity and above all support the people in the Ukraine!

Why not make energy from water. Not talking about hydrogen gen here.

We have been running cars on water since the 1950’s. Large energy players buy the patent then shelve it or inventors bullied by Govt interest groups as threat to national security.

The technology is there but hidden from us.

Why are we even talking about fossil fuels/batteries and the like??