In attempting to study the maps created and used during spatial design, we could not find a suitable framework or theory that describes the spatial design process—and the actual concrete actions involved—with the necessary degree of clarity and simplicity. Despite sharing many elements, existing theories focus on different aspects of spatial design. They thus complement each other but also leave inconsistencies and unclear relationships between concepts of the theories.

Therefore, we set out to propose our own conceptual framework that—in true cartographer fashion—synthesises the ideas of the previously proposed theories in a simple and consistent manner, but without losing their essence. Hopefully, we will be able to publish it soon.

Existing Theories of the Spatial Design Process

The main theories we considered so far are listed below. Our focus is on theories with a high degree of action-orientation1. That is, process-oriented, instructive, theories that describe the concrete steps, phases, and process flows of spatial design.

- Schoenwandt’s planning theory of the third generation (2002; 2016)2

- Grunau’s questionnaire for dealing with complex problems (2009)3

- Van den Broeck’s outline using trajectories (2010)4

- Nollert’s gameplay instructions (2013)5

- Carmona’s place-shaping continuum (2014; 2021)6

- Prominski’s interplay of design ‘moments’ (2019)7

- Von Seggern’s abstract process sketches (2019)8

- Kretz’s cosmos of design (2020)9

If there is any relevant work we have missed, please do let us know!

A Generic Language

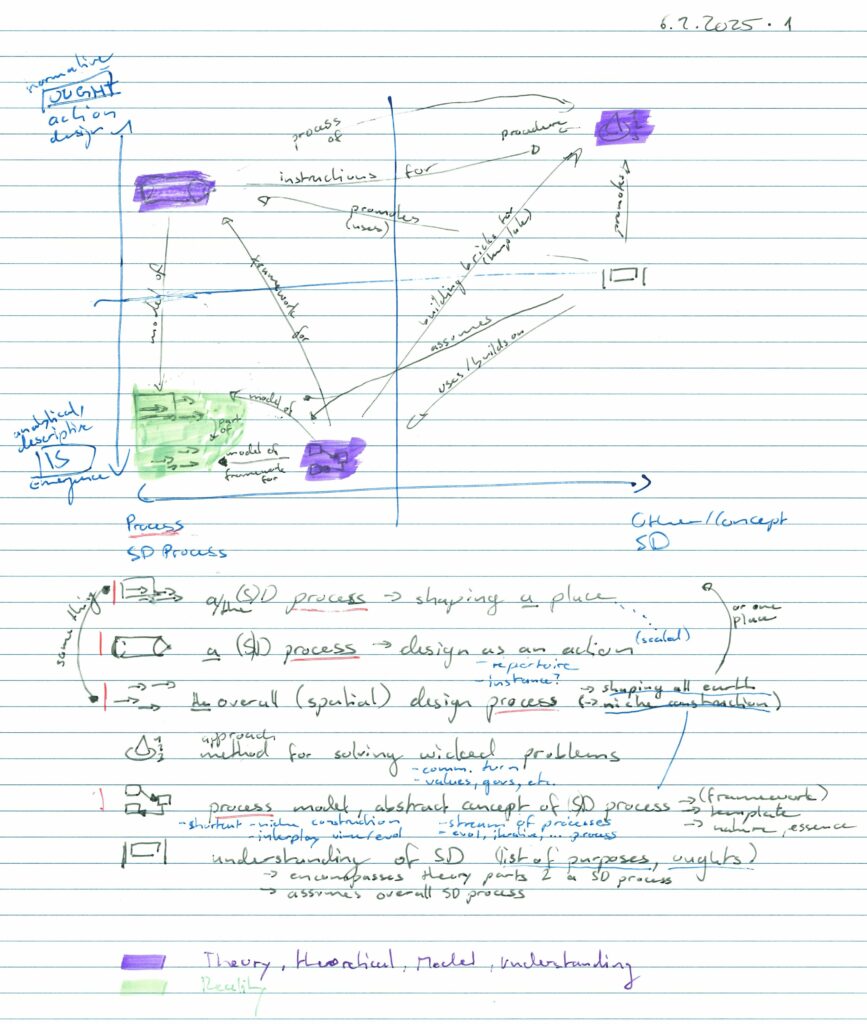

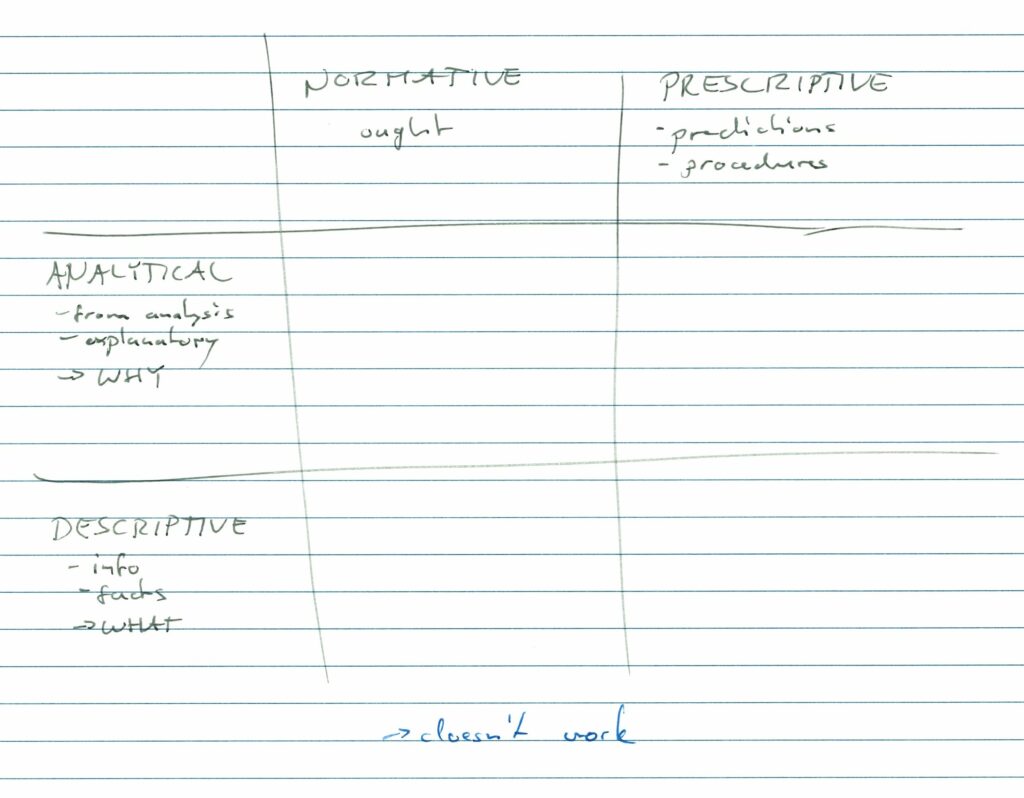

We intend to use the developed conceptual framework as an analytical framework: It allows us to model the spatial design process and locate maps within this process.

Additionally, the conceptual framework has an explanatory purpose: It provides arguments for why certain aspects of spatial design processes are the way they are. For example, it provides an explanation as to why spatial design processes are attributed with contradicting characteristics, including exploratory, evolutionary, incremental, and iterative.

However, the framework’s real value lies in its use as a generic language to reflect on spatial design theories and processes. Talking about the design process itself is crucial in spatial design. Collaboration and true co-design can only happen if the design process is made explicit.5 The framework provides the basic vocabulary needed to do so.

This vocabulary needs to be generic for two reasons:

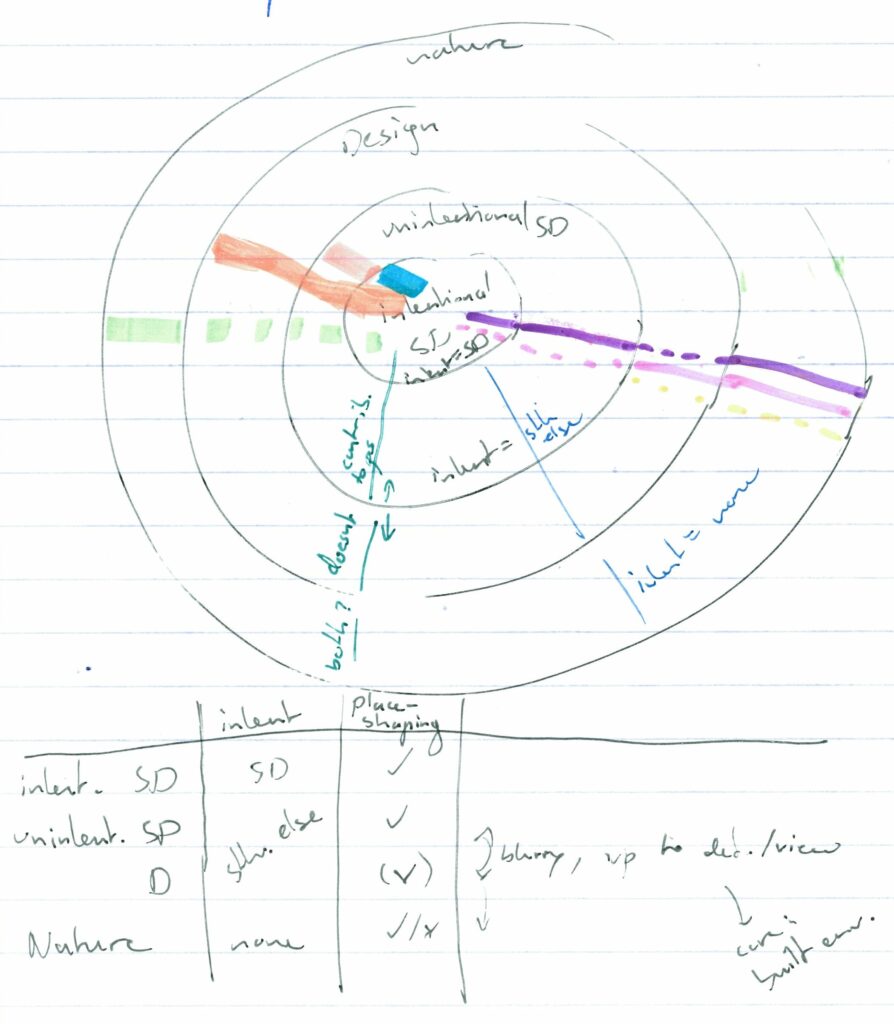

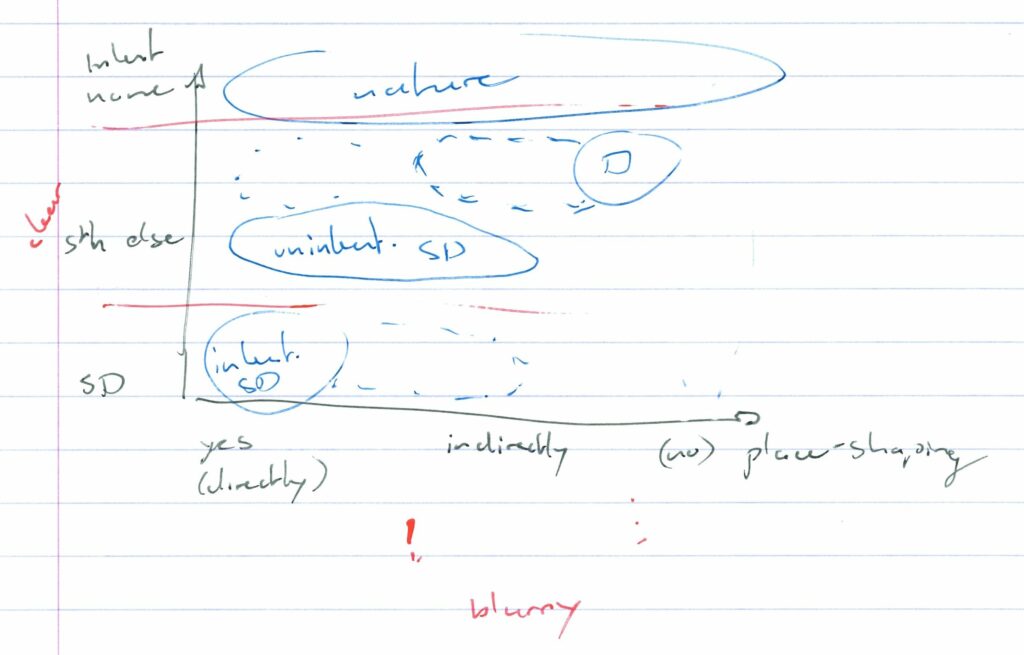

First, spatial design is an emergent process. Spatial design processes cannot be defined or known in advance. This means that any description of such a process will need to be unique and customised. A language definition therefore only makes sense on an abstract level.

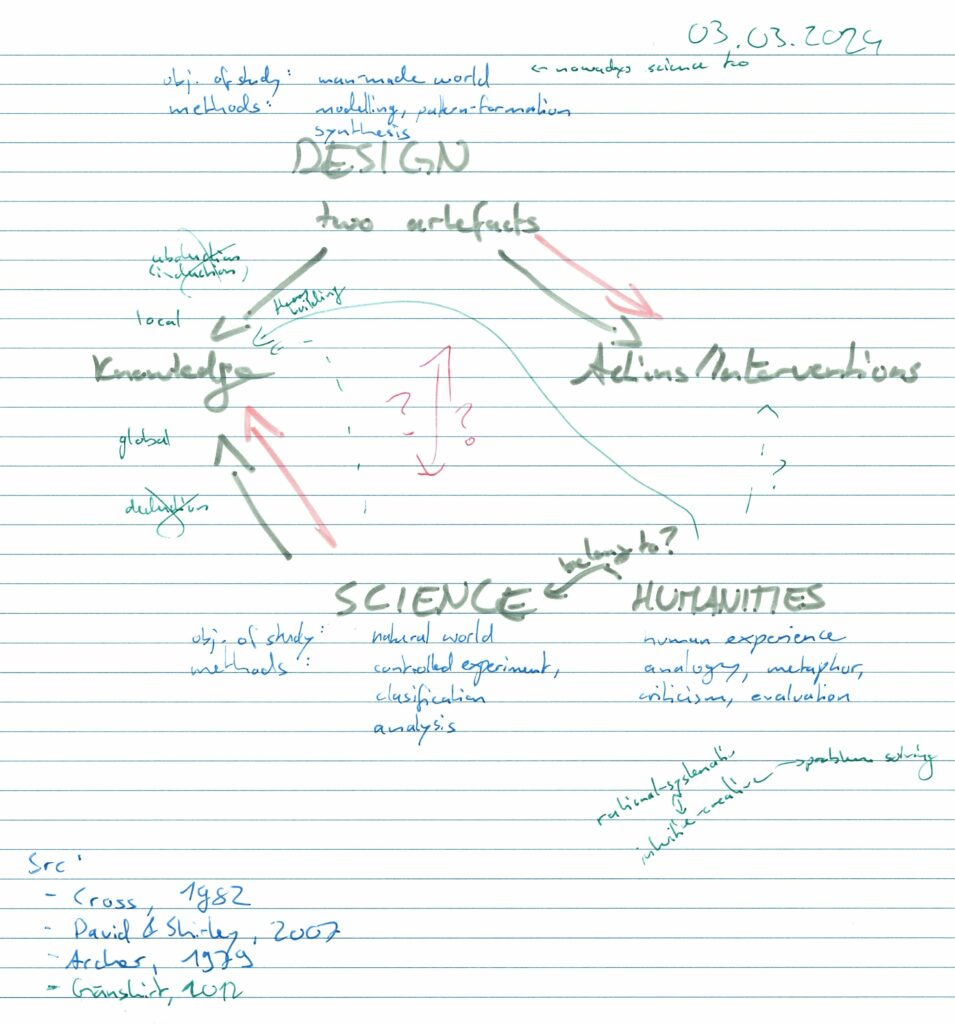

Second, spatial design is interdisciplinary. Moreover, the design approach is not restricted to the domain of spatial planning, as an as an account by Narelle Yabuka (2024) illustrates. Approaches like research through design7, designerly ways of knowing10, and inquiry by design11 show that the design approach is a general way of understanding. A language for spatial design must therefore be capable of describing design processes outside the planning domain as well. This means that concepts and relationships need to be defined at an abstract level and without reference to spatial content.

A Visual Language

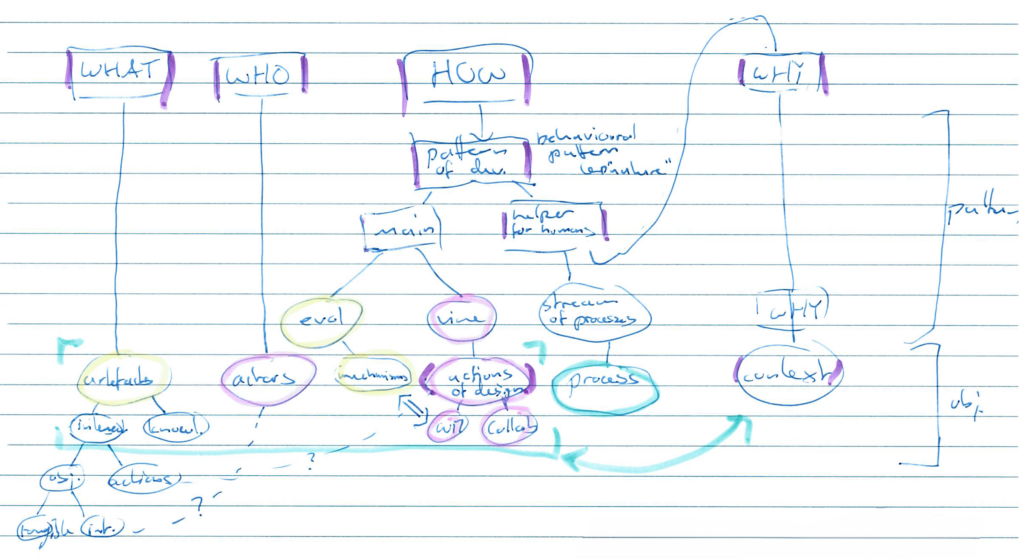

Theories that model the planning process have usually been materialised as a theory map: a visual representation of the theory. It depicts all the theory’s concepts and how they relate to one another. Similarly, our conceptual framework provides a generic visual language to map spatial design processes.

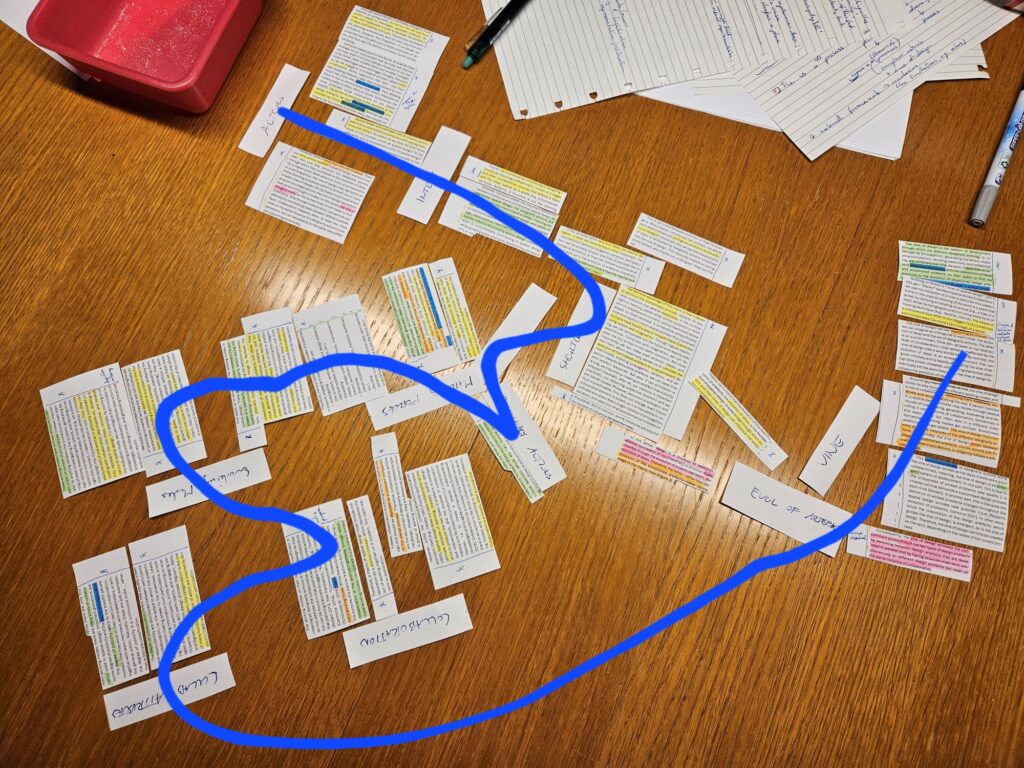

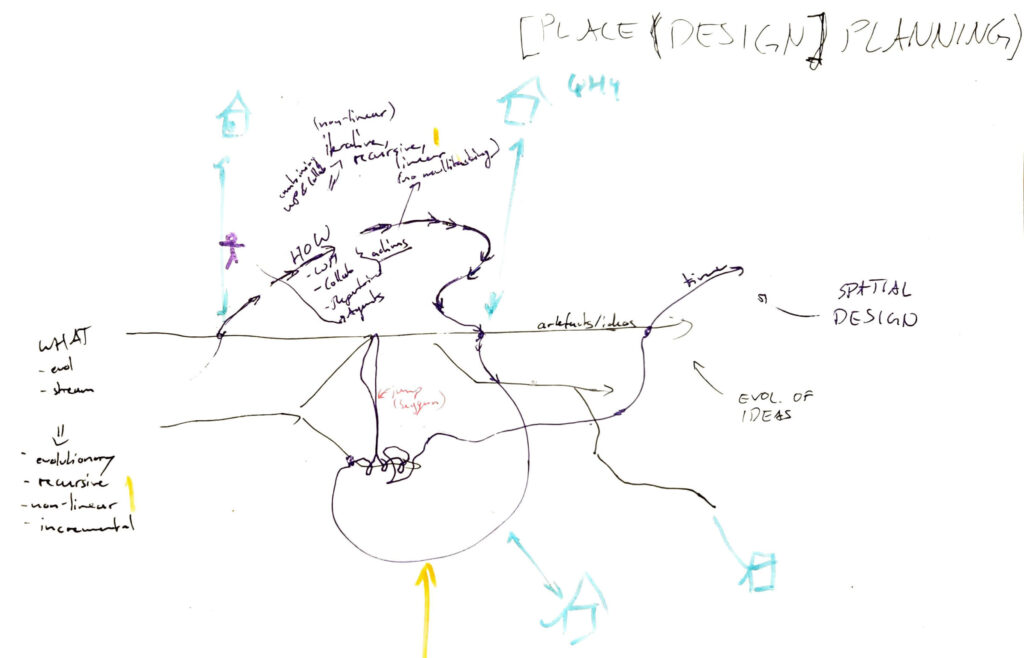

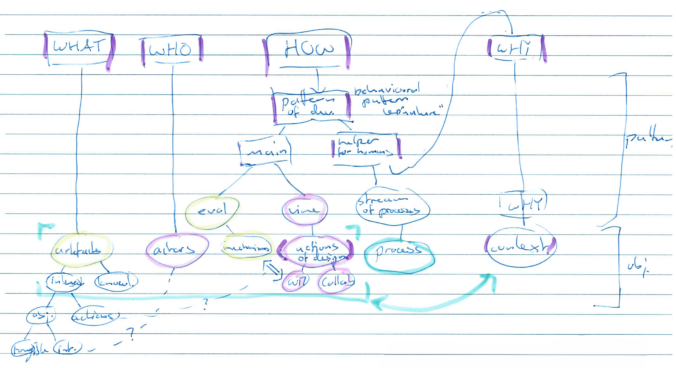

In the process of developing such a visual language, we have and still are creating numerous sketches and theory maps. Similar to how spatial planners create countless sketches, maps, and plans during their design process. The gallery below showcases selected examples.

References

- Levin-Keitel M, Behrend L. The Topology of Planning Theories: A Systematization of Planning Knowledge. Springer; 2023. ↩︎

- Schönwandt WL. Planning in Crisis? Theoretical Orientations for Architecture and Planning. Routledge; 2016. doi:10.4324/9781315600765 ↩︎

- Grunau JP. Lösen komplexer Probleme: theoretische Grundlagen und deren Umsetzung für Lehre und Praxis. 1. Aufl. Der Andere Verlag; 2008. ↩︎

- Van den Broeck J. Spatial design as a strategy for qualitative social-spatial transformation. In: Strategic Spatial Projects: Catalysts for Change. 1st ed. Routledge; 2010:87-96. Accessed August 19, 2023. https://www.routledge.com/Strategic-Spatial-Projects-Catalysts-for-Change/Oosterlynck-Broeck-Albrechts-Moulaert-Verhetsel/p/book/9780415566841 ↩︎

- Nollert M. Raumplanerisches Entwerfen. ETH Zurich; 2013. https://www.research-collection.ethz.ch/handle/20.500.11850/71036 ↩︎

- The theory was first published in a paper:

Carmona M. The Place-shaping Continuum: A Theory of Urban Design Process. Journal of Urban Design. 2014;19(1):2-36. doi:10.1080/13574809.2013.854695

Later, the theory has been elaborated in a textbook:

Carmona M. Public Places Urban Spaces: The Dimensions of Urban Design. 3rd ed. Routledge; 2021. doi:10.4324/9781315158457 ↩︎ - Prominski M. Design research as a non-linear interplay of five moments. In: von Seggern H, Prominski M, eds. Design Research for Urban Landscapes: Theories and Methods. Routledge; 2019. ↩︎

- von Seggern H. Crossing fields: designing and researching Raumgeschehen. In: Prominski M, von Seggern H, eds. Design Research for Urban Landscapes: Theories and Methods. Routledge; 2019. ↩︎

- Kretz S. The Cosmos of Design: Exploring the Designer’s Mind. Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther König; 2020. ↩︎

- Cross N. Designerly Ways of Knowing. Springer-Verlag; 2006. doi:10.1007/1-84628-301-9 ↩︎

- Zeisel J. Inquiry by Design: Tools for Environment-Behaviour Research. Reprint. Cambridge Univ. Press; 1984. ↩︎

Leave a Reply